Pinot Noir ............................... Cabernet Sauvignon

Food and Wine

This topic has had a lot of press lately and there seems to be a great deal of conflicting information and attitudes out there. The basic principle of food and wine matching is very simple—if it works for you, it’s good.

Both wine and food are things which bring us pleasure, and there’s no point in developing anxieties over serving just the right this or that with just the right that or this. We live in an increasingly cosmopolitan world, and so it’s worthwhile looking at the old guard before we toss it out.

The most classical,they are actually known as “classical matches”,form of wine and food matching is to marry the wines of a region with the foods of a region, based on the argument that the two evolved together. They have a sort of community relationship. Some examples are the Riesling of Alsace with choucroute garni; Barolo with truffles and game; Muscadet with oysters; red Bordeaux with lamb.

What we soon observe when looking at classical matches is that most of them observe some very basic principles that can be applied to other wine and food matches. There are a few worthwhile rules of thumb to observe to avoid truly disastrous meals and getting at those rules is quite simple—we only have to go back to the basic components of wine and observe how they interact with the various components of food.

Weight, Intensity

The central consideration for the food and particularly to sauces and cooking styles: we match weight to weight—light to light, heavy to heavy. Wine should not be heavier. Primary issue here is balance. Full bodied wine matched with full bodied food. Intensity can act as a counterbalance to weight particularly evident with rich, fat laden foods matched with light-bodied, but intensely flavoured wine in this case we are looking for contrast.

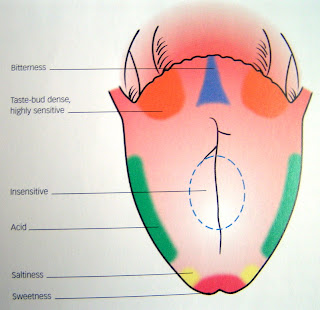

Acid, Salt, Sweet, Bitter, Tannin, Umami

Acid

Some regard acidity as the most important consideration after weight, and sometimes before weight.

It functions, in both wine and food, as a counterbalance to sweetness, and to fat where both sweetness and fat coat and tire the palate, acid refreshes and cleans. It is therefore an essential component in wines matched to rich dishes such as those based on butter or cream, oily foods such as deep-fried goodies, oily fish and buttery shellfish, and also cuts through high salt foods such as oysters.

Acidity can function as well as a mirroring taste for relatively high acid foods such as tomato-based dishes, and dishes with lemon and capers. Acidity in food often clashes with tannins in red wines.

Saltiness

For particularly salty dishes, typically look to a mix of sweetness and acid. Salty old cheeses usually require sweet wine match. It will also accentuate the effect of alcohol. Acidity cuts saltiness (you lick the salt before you bite the lemon when doing tequila shots).

Sweetness

Perception of sweetness is governed by two factors. The level of residual sugar, and the level of balancing acidity. Sweetness can be matched with mildly spicy food because sweetness can mask spiciness. Sweetness can offer matching flavours for moderately sweet dishes.

Sweetness is a fine foil for salt: as in old cheeses; and also as in dishes based on soy. In food, sweetness needs to be matched with a wine at least as sweet or the wine may taste thin and acid. Weight is still important, but sweetness level even moreso.

Tannin and sweetness rarely successfully match (red wines end up tasting drier).

Tannin and Bitter

Typically bitter wines can be matched with like flavours especially grilled or charred foods how ever this can also cause too much bitterness and is a tricky one. Particularly tannic wine typically require meats of dense texture. Chewiness and protein moderates tannin. Tannic wines are diminished with rare meats due to the iron in blood. The fat of meat also coats the mouth and softens tannic impressions.

Umami

The so-called fifth taste is associated with mouthfeel and the effects especially of glutamates in the mouth, msg especially and salt. The concept is ancient and Japanese and has been variously translated, the current standard seems to be deliciousness. Ask yourself: given all of the other components of a wine, is it also delicious? Does it have a moreish quality; do you say, yummy, that tastes good I'd like another sip?

Language Development

Intensity (Aroma)

This is a word which tends to present difficulties early on, and it probably should. The reason it probably should is simple it is a relative term, and to use it effectively, you have to be able to relate it to a decent number of wines. The useful relative terms are as follows. Not aromatic; moderately aromatic; highly aromatic. This seems rather boring, but there are other ways to speak of these. For a wine which is not aromatic which presents very little aroma at the time of

primary olfaction, we occasionally call the wine shy, or sometimes dumb. We borrow this language from the human personality and by doing so we want to explain that the wine is not expressive, not forthcoming, or is introverted.

Moderately aromatic wines occupy the great middle ground neither introverted nor extroverted, they are wines which do not call attention to themselves, but do have something to say, and say it at a normal conversational volume. These wines may be subtle, balanced, seductive. Highly aromatic wines are extroverts, and they have a tendency to shout, wear tuxedo tshirts etc. Very often, their intense aromas are their most interesting trait and the language we use often borrows from the extroverted character type are words like aggressive, showy, forthright, forward, exuberant.

Pinot Noir

Some believe this to be a very ancient grape variety native to France. For some, it is the greatest of all grapes, capable of providing the most ethereal, spiritual, intense pleasure. At the same time, the most ardent lover will admit that Pinot Noir is also often the worst of wines, source of nothing but disappointment. Yet they keep drinking it, looking for that one bottle in a thousand which is truly sublime. Others simply give up on it, acknowledging that it isn’t really worth the trouble though most of them move on to grapes with similar tendencies like Italy’s Nebbiolo, with which Pinot is sometimes compared, though not for flavour for uniqueness.

It is also a tough grape to grow, fickle, false, unstable, changeable, unfaithful the same words can be applied to the grape once it hits the bottle.

Because of its tendency to betray both its grower and its drinker, it is sometimes known as the heartbreak grape or the gypsy grape.

In the Vineyard

Features

Compact bunches with occasional variation in skin thickness and berry size.

Buds early and ripens early.

Vines do not live long—50 years is very old for Pinot.

Variety is unstable and prone to genetic mutation there are many clones, for example many different clones of Pinot producing wines with different characteristics.

Susceptibility

Rot is a significant problem—especially in the fall after rain. Early budding makes it vulnerable to spring frosts. Vines are relatively short-lived.

Soils and Climate

Prefers well-drained, deep soils, especially with limestone subsoils. Likes the chalky, calcium rich soils of champagne. Prefers cooler, marginal, temperate sites. In warm climates, it tends to flatness and cooked flavours, losing its essential aromas.

In the Winery

Vinification and Ageing

Chaptalization common in Burgundy. Sometimes new oak is used for maturation, but tradition suggests that this can overwhelm what is an essentially delicate wine older oak may be best.

New world tends to longer macerations to extract colour and tannin. Variety is typically low to mid tannin and medium to low acid with usually pale ruby colour.

Aromas and Taste

Fruit: strawberry, strawberry jam, black cherry, plum, raspberry.

Earthy: leather, game, mushrooms, beetroot, barnyard.

Floral: violets.

Low-medium tannin, medium acidity, medium body.

Noted Regions

Spiritual home is central France in Champagne and Burgundy for still wines, it is Burgundy foremost, especially the villages of the Cotes de Nuits.

Other regions are Russian River Valley and Carneros in California, as well as the Santa Lucia Highlands. Willamette Valley of Oregon. New Zealand especially the Nelson region and Central Otago. Parts of Australia the Yarra Valley and Tasmania.

Cabernet Sauvignon

Along with Merlot, the most important of the international varieties it is planted everywhere although it does best in moderate to warm climates cooler climates often don’t have enough heat for ripening and often result in harder green flavours.

In the Vineyard

Features

Thick skins and loose bunches—buds late and ripens late.

Small, blue-black berries with very large pips and small amount of pulp.

Wood tends to be tough.

Susceptibility

Powdery mildew (oidium) a problem in some climates and rot in wet, cool autumns.

Vine, though is generally hardy and adaptable.

Soils and Climate

Quite adaptable, but generally needs a warm soil because of late ripening.

Bordeaux—deep, gravely soil.

Coonawarra—limestone subsoil with red loam on top. Also does well in rich alluvial soil of the Napa Valley.

In the Winery

Vinification and Ageing

Natural affinity for new oak (vanilla and spice).

Durable and can stand high temperature fermentation and long-ageing in oak as well as extended maceration after fermentation.

Ages very well especially in Bordeaux.

Aroma and Taste

Fruit: black currant (cassis), black cherry, blackberry.

Earthy: cigar box, tobacco.

Herbal: mint in US, eucalyptus in OZ.

Can have vegetal, bell pepper streak if a little under ripe.

Also tannic, concentrated, full-bodied, deep color.

Noted Regions

Spiritual home Bordeaux, France, especially the left bank districts of the Medoc, Graves and the Haut-Medoc. More specifically, the Haut-Medoc communes of Pauillac, St.-Estephe, St.-Julien and Margaux as well as the commune of Pessac-Leognan in the Graves district a little further south.

Other regions California especially the Napa Valley. Australia especially Coonawarra. Certain parts of Italy and Spain also excel with CS as do Washington State, Argentina, and Chile.