The History of Wine

Place in Consciousness - Religious and Cultural

From its most ancient origins, wine has been filled with sacramental meaning and has often operated as a form of connection with spiritual realms which are beyond the day-to-day lives of human beings.

It was, too, a form of medicine, charged with healing powers, dulling pain, providing sleep to the insomniac, aiding in the digestion of food. By extension, it was, as well, a form of spiritual medicine, giving comfort, courage, renewal, lifting inhibitions, and was capable of peeling back the veil separating humanity from the sacred a.k.a. getting pissed drunk.

Many cultures, for example, have concepts of ‘sacred drunkenness’ though it is not always wine which is used to reach this state.

In mythological terms, we see it linked often with blood in the Christian Eucharist as the stand-in for the blood of Christ, as the blood of Dionysus in Greek myth, or of Bacchus in Roman myth.

In the medical world, it worked as an antiseptic mixed with water, it made the water drinkable; and the alcohol in it could clean wounds. It has long had the cachet of luxury, largely because from earliest times it was available only to a privileged few. In the near east, grain was the standard crop and ale the beverage of the masses. Later, with the Greeks and the Romans, we see the democratization of wine.

Origins and Movements - Phoenicians, Greeks, Romans

There are many different species of grapes some native to Europe and the Middle East, some to North America, and some to Asia.

What we are interested in, however, is the Euro-Middle Eastern species known as vitis vinifera, simply because the species native to other parts of the world are very rarely cultivated as wine making grapes, though they do have a certain significance to the world of wine.

Vitis vinifera translates as the ‘wine bearing grape’.

There is general agreement among historians about roughly when and where the vine was first cultivated. Current speculation suggests that this first happened in the area known as Transcaucasia in the foothills of the Caucasus mountains of present-day Georgia and Armenia. Carbon dating of petrified seed or pips suggests that this was likely around 7 000-5 000 BCE ???

From there knowledge of winemaking, viticulture, and the appreciation of wine spread along trade routes into the Middle East. The important Tigris and Euphrates rivers have their sources in the Caucasus range. Into Mesopotamia where Sumerian culture was located, to Egypt and other cultures of the Middle East, such as Phoenici.

Phoenicians from the land which is today Lebanon were a people who traded and expanded their empire. They founded Carthage in North Africa, later in Spain and spread their influence all over the Mediterranean basin. They likely were the first to bring the vine to Western Europe the cultivated vine, that is.

Greeks likely first discovered wine through the influence of Middle Eastern cultures, with whom they traded, but Greek culture adopted the vine and wine so much so that along with olive oil it became their primary product for export.

Greeks took the vine to Italy, a place they found conducive to the vine, and to France where they founded a colony at present-day Marseilles.

Though Greek influence is still evident in France, it is much more obvious in southern Italy, where the names of a number of grape varieties pay homage to the Greek inheritance Greco, Grechetto, Aglianico. Roman culture expanded the vine immensely, and the expansion of the Roman Empire brought the vine to some of the famous sites of today to Burgundy, to Bordeaux, to Champagne, Alsace, the Rhine and Mosel in Germany, along the Danube.

Everywhere they went, they planted the vine essential food for the army.

Impact of Disease, Trade, Exploration

Post-Roman Empire, through the Middle Ages, viticulture was kept alive by the Church in Europe, most especially by the Benedictine and Cistercian Orders.

The Benedictine Order was Europe’s most powerful and spread out all over Europe and took viticulture with them. Wine was essential not just for the Mass, but also as a daily food in a time before potable water was widely available

It was also, of course, a saleable product, and contributed revenue to the Orders.

The Monastic Orders of the Middle Ages operated as multinational corporations there were, for example, over 1 000 Benedictine monasteries spread around Europe, and in a pre-industrial age, they generated income through agriculture.

An essential contribution of the Benedictine order was written documents on the techniques of viticulture. Also significant was the Cistercian order (founded by Saint Bernard), an ascetic offshoot of the Benedictines who believed that work, especially agricultural work, was a form of devotion, and who tried to be largely self-sufficient, making their way through their work.

It is important to remember that during the Middle Ages, the Church had much greater influence over European consciousness than it does today and the Monasteries were able to amass large and valuable land holdings through donations from wealthy people fearful of the fate of their eternal souls.

Opening of the New World brought new opportunities for viticulture in late 15th and early 16th centuries and we see the vine arrive in South America with the Spanish, the explorer Cortes is usually given the credit for introducing the grape, and Portuguese and then into North America with the English, French, and Spanish.

If nation states wanted to increase the size of their holdings, develop colonies, increase wealth and power by exploiting resources of new lands, the church went with them. Whatever the motives of the church were to expand the reach of the word, to save pagan souls, increase their own wealth and power they invariably took the vine with them because it was essential to the communion service and essential to the laity as well. The grape they brought known as the Mission grape, and there are still some plantings around.

South African plantings begin in the 17th century as the Dutch plant in the Cape at a way-station for East Indian trade routes. In the late 18th century, the English bring the vine to Australia hoping that country would become England’s vineyard as well as her prison. The most significant event of the 19th century, and perhaps history’s most important event after the initial cultivation, is the arrival of a variety of diseases in the latter part of the century in European vineyards.

It all began with mildew issues,powdery and downy mildews and culminated with the arrival of a vine louse dubbed phylloxera vastatrix, vastatrix translates as ‘ravager’ or ‘destroyer’. The louse most likely arrived in the Mediterranean basin in the 1860s at the mouth of the Rhone River which was probably the most densely concentrated area of vines on earth, Mecca for the louse. Infestation is fatal for the grape vine, because the louse feeds on the roots of the vine and in feeding, injects a poison into the roots, which is taken up by the vine’s internal system.

The louse made its way slowly east, west and north and eventually affected every part of Europe. It is hard to imagine scale of this, but one historian estimates that there may have been as many as 11 billion vines in France alone.

Eventually it was discovered that the louse was native to Eastern North America and that the native species of vines which grew there none of which are vitis vinifera, and none of which make very good quality wine had developed near immunity to the louse. European vines could be grafted onto these American roots and their character would not be fundamentally altered.

But the effect of phylloxera was lasting and in some ways beneficial because in the wake of phylloxera, there was widespread fraud, especially in traditional wine producing countries which experienced a shortage of wine and fake products, such as wine made from imported raisins or weird mixtures of beet juice and sugar were sold with labels suggesting they came from famous growing areas, such as Bordeaux or Burgundy. This led to government action to prevent fraud, and protect the famous names of origin, regulations and processes to guarantee the authenticity and, in some cases, the quality or potential quality of wines from specific places.

Government regulation has its beginnings in France in the 1930s with the creation of the appellation of origin laws: the establishment of the AOC (appellation d’origine controlée—ie. controlled name of origin) would influence the European Union’s approach to agricultural regulation and would echo throughout the world.

Today many products have their authenticity defended by such laws wine, for sure, but also products like cheese, beer, and even certain breeds of livestock which must be raised in particular ways and in particular places.

On a positive/negative note, it changed the constitution of the European vineyard as growers planted varieties with different characteristics mostly high yield (quantities) and good disease resistance and this led to the loss of certain characterful varieties which were difficult to grow.

Estimates vary, but there may be as many as 15 000 different varieties of vitis vinifera, but the wine world is dominated by only a small handful of varieties.

Tasting Theory Mystique

Sometimes people are filled with fear over the prospect of tasting wine or more about the prospect of communicating what it is they are tasting. The way over that fear is to begin to understand that there are techniques of tasting, and that tasting is a craft that is learned, not some in-born trait that some people have and some people don’t. The entire thrust of the ISG’s (International Sommelier Guild) approach to tasting can be summed up in one word: DISCIPLINE.

Tasting technique is developed through practice in two areas.

1. actually putting wine in front of your eyes, under your nose, and in your mouth.

2. and then developing a vocabulary to describe what you see, what you smell, and what you taste.

At the beginning, this may well detract from your enjoyment of wine because it breaks down into seemingly disunified bits and pieces what is ideally a harmonious and complete experience which is usually simply liked or disliked very few of us like to explain why we like something or don’t like something. But looking at things closely from different angles allows us to ask more questions and ultimately may well provide us with expanded horizons or allow us to choose to expand our horizons and take us away from being relatively simple consumers to being intelligent, informed consumers.

The Tasting Sheet

Appearance Clarity

Relatively simple and straight forward is the wine clear? or is it hazy? or cloudy? Wines will typically either be Transparent (you can see through it) or Opaque (you can’t see through it).

Intensity

We also ask how intense the colour is, is it bright or is it dull; is it pale or is it deep

Colour

Seems relatively simple, but people are generally less familiar with colours than they like to admit reds are red and whites are yellow; but we will learn some differences as the course goes on; initially ask yourself about the quality of the colour; is the wine transparent, or is it opaque.

Nose Condition

This asks whether the wine is healthy or faulty. As you encounter more faulty wines, and recognize their characteristic smells, you will develop confidence making this assessment.

Intensity

This simply asks how strong the aromas are. They will be described as High, Moderate, or Low.

Flavour Character

This simply asks what it is that you smell. Usually just 2-4 descriptors are useful though some people use too many and end up being ineffective -being too broad. When we smell a wine, we vacuum up volatile aromatic chemicals which are dissolved in a mucous membrane and interpreted by our brains specifically in the olfactory bulb. Smelling through our nose is sometimes called direct olfaction. Below is a list, not an exhaustive one, of common wine aromas. Please notice that the aromas are arranged in categories a la Russian dolls. Always, when tasting, begin with the most general category before getting more specific.

Fruity Smells:

There is a wide range of fruity smells associated with wine, and many of them we will encounter at some point during the course. For simplicity, we can break down the fruity smells of wine into a set of categories.

Citrus Aromas:

lemon, lime, grapefruit, orange.

Berry Aromas:

These can be broken down into red berries like strawberry, raspberry and red currants and black berries like blackberry and black currants

Tropical Fruit Aromas:

Pineapple, mango, various melons, bananas, lychee.

Tree Fruit:

Cherries, plums, apricot, peach, apple.

Dried Fruit:

Confected fruits like strawberry jam, figs, prunes, raisins, sun dried tomato. Vegetable Smells:

Bell pepper, eucalyptus, grass and straw, mint, asparagus, green beans, olives, tea, tobacco.

Woody Smells:

Cedar, oak, vanilla, coffee, toast.

Caramelized Smells:

Honey, butterscotch, chocolate, molasses, soy sauce.

Earthy Smells:

Musty, muddy, tar, mushrooms of various types, forest floor and humus, manure and various other excremental smells.

Spicy, Herbal, and Nutty Smells:

Hazelnut, almond, coconut, licorice, black pepper, brown spices such as cinnamon, nutmeg, allspice and cloves.

Floral Smells:

Rose petals, violets, fruit blossoms such as peach and orange.

Dairy/Bakery Smells:

Yeast, bread dough, butter, cheese.

Chemical Smells:

Wet cardboard, sulphur, hydrogen sulphide (rotten egg), rubber.

Wine Flaws:

Oxidation, cooked and stewed smells, mould, cork, vinegar.

Aroma vs Bouquet (ie. Development)

This relatively old distinction can cause a great deal of consternation, but there are easily understood distinctions to be made easy intellectually, but perhaps more difficult practically. As wine matures, it begins to take on different smells the same wine at 2 years of age and at 12 years of age will smell different. The distinction between aroma and bouquet is designed to address this simple fact. What is most useful to remember is that aroma is the smell a wine most typically offers in youth, whereas bouquet is the smell of a mature wine; it is, in other words, a smell associated with the development of the wine over time some tasting sheets will use the word development instead of aroma/bouquet.

Aroma is most importantly linked with the aromatic signatures of the grape variety its the specific characteristics. Throughout this course, we will look at the major aromas associated with individual grape varieties and they will become your anchors for identifying wines in blind tasting situations. Aromas, then, are fruit smells and other common smells associated with a variety.

Later in our education we will come to call these smells primary aromas. The smells associated with bouquet tend toward the earthy, even the subterranean, and are ultimately more complex and elusive than the primary aromas mushrooms, truffles, forest floor, nuts.

In bouquet, the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. Aroma reaches out for things above the ground it is air, pure Eros.

Bouquet reaches beneath it is earth, sex and death, the smell of the Fall.

Later in our education, we will come to call bouquet by the name tertiary aromas.

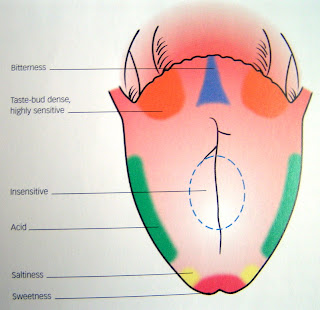

Taste (Palate)

Sweetness:

Some wines are sweeter than others, and we will begin to understand sugar levels in wine. The standard degrees of sweetness are as follows:

Dry—Off Dry—Medium Dry—Medium—Medium Sweet—Sweet Acidity: All wine is acidic; what we are interested in doing is developing a sense of the degree of acidity in the wine from low to high. We will develop this by experiencing wines side-by-side with different levels of acidity.

Tannin:

A natural constituent of the skins of grapes and also of wood barrels, all wine contains some tannin, though it is in red wine that we experience it most; it produces a drying sensation on the teeth and gums. What we are interested in is examining the level of tannin in the wine from low to high.

Flavour Character:

Here we are interested in testing and confirming what we experienced when we first smelled the wine. The mouth warms the wine and the aromas travel up into the nasal cavity through the back route. This is sometimes called Retro-olfaction and we have access to this when we breathe out after spitting or swallowing wine. Also ask yourself how intense those flavours are.

Body/Alcohol:

All wine contains alcohol in the range of 5-17% for unfortified wines, higher for fortified wines. Alcohol provides the body of the wine. When we speak of body with respect to wine, we are asking ourselves how thick or thin, full or light the wine is. A good parallel is provided by milk: think of skim milk as light-bodied, whole milk as medium-bodied, and cream as full-bodied

Length:

Here we are interested in the finish of the wine and will ask ourselves how long the flavours last, what we call length or persistence.

Summary Issues

Balance:

This is perhaps the most important issue. Quality wines are marked by a balance of the constituent elements of acid, sweetness, tannin, alcohol, flavour and length. No single element should dominate the profile of the wine.

Quality:

We will begin to examine issues of quality in wines and rate them according to our perceptions from poor to excellent.

Maturity:

We will begin to understand the meaning of maturity and apply it to wines and come to understand the difference between age and maturity. We will ask ourselves whether the constituents of the wine indicate that it may benefit from further cellaring or whether it is currently drinking at its peak.

White Wine Vinification Fundamental Steps

Step 1.

Crushing of White or Black Grapes

Variables: If black grapes employed, skins and juice must be separated. If coloration of juice is not desired, most commonly white grapes are destemmed at the time of crushing.

Step 2.

Separation of Free-Run Juice

Variables: This is usually considered the finest quality juice, kept separate from press-wine.

Step 3.

Pressing of Solids

Variables: Choice of press, use of press wines?

NB: PRESSING OF WHITE WINE IS PRE-FERMENTATION!!!!!

Step 4.

Settling and Clarification of Juice pre-fermentation (clear juice ferments better than very cloudy juice)

Step 5.

Alcoholic Fermentation

Variables: Yeast culture choice or use of wild yeasts, duration and temperature of fermentation (generally cooler fermentation temperature than for red wine). Choice of fermentation vessel, size and material (i.e., stainless steel, concrete, wooden barrels).

Step 6.

Malolactic Fermentation

Variables: Malolactic can be included or prevented. Significantly impacts on impression of acidity and flavor enhancement.

Step 7.

Ageing

Variables: Duration of ageing period, choice of vessel, inert or porous, type of wood, age and qualities of wood, ageing on yeast lees or not.

Step 8.

Fining and Filtering (Clarification)

Variables: Fining or not (Materials used?), filter or not (Materials/method used?), filter (How many times?)

Step 9.

Bottling/Packaging

Variables: Choice of container, labeling, closures

Red Wine Vinification Fundamental Steps

Step 1.

Crushing of Grapes

Variables: Separation of grapes from stems (no or full or partial de-stemming)

Step 2.

Addition of Yeast

Variables: Selection of yeast used, native or cultured Chaptalization in cool climates for sugar level compensation (addition of cane or beet sugar) in certain years approved by AOC

Step 3.

Alcoholic Fermentation (Juice and skins together)

Variables: Duration and temperature of fermentation, pumping over or punching down cap – all influence color and flavor extraction from skins. Choice of fermentation vessel, size and material (i.e., stainless steel, concrete, wooden vats) Carbonic maceration for Gamay grape in Beaujolais – whole berry fermentation in closed vessel increases fruit profile = bubblegum/candy like

Step 4.

Separation of juice and Solids Post-Fermentation

Step 5. Pressing of Solids

Variables: Choice of style of press, press wine kept separate, may be used or not to some degree in final blend

NB: PRESSING OF RED WINE IS POST-FERMENTATION!!!!!

Step 6. Malolactic Fermentation – Almost Universal in Red Wine Making

Step 7. Ageing Pre-bottling

Variables: Duration of ageing, choice of vessel, inert or porous, type of wood, age and qualities of wood Pigeage – punching down the cap – encourage extraction of color & tannins and aeration for deep red wines

Step 8. Bottling

Variables: Choice of container, labeling, closure.

Use of Sulphur Dioxide (SO2) can be employed at ALL above stages, from freshly harvested grapes to newly bottled wine to act as an antiseptic and anti-oxidant.

No comments:

Post a Comment